This is a huge topic and anxiety around understanding the needs of young people and their views on sexual orientation and gender is something we work with frequently.

A person’s sexual orientation, or sexuality, is the part of their identity that relates to who they find attractive/who they fancy. Although it’s in the name, the attraction to other people does not have to be sexual, it could be romantic. Some people are attracted to a particular gender/genders, some people are attracted to who the person is (their morals, values, humour, intelligence, etc), and for some it’s a combination of the two. Attraction can feel different for different people; it can involve wanting to be around a person more, thinking about them when you are not with them, “butterflies” in your stomach, feeling giddy or nervous when you are together and more.

Allosexual: A person of any gender or sexual orientation who experiences sexual attraction

Aromantic: A person of any gender or sexual orientation who experiences little, or no, romantic attraction. Aromantic people may still experience other types of attraction, such as sexual or physical attraction.

Asexual: A person of any gender or sexual orientation who experiences little, or no, sexual attraction. Asexual people may still experience other types of attraction, such as physical or romantic attraction.

Biromantic: A person who experiences romantic attraction to more than one gender but little or no sexual attraction.

Bisexual: A person of any gender who experiences attraction to people of their own gender and other genders.

Demisexual: A person who only experiences sexual attraction to people they have a close emotional connection with.

Gay: Traditionally this word has meant a man who is attracted to other men. Today, people of other genders use this word too, so the word gay describes a person who is attracted to other people of the same gender.

Heterosexual/straight: A person who is attracted to people of a different gender.

Lesbian: A woman who is attracted to other women.

Pansexual: A person of any gender who is attracted to people of all genders.

Queer: Historically this word was used as a negative insult, however many people feel they have reclaimed the word to have a positive meaning. Some people use it as a collective term for LGBT+ people, and some use it to explain their gender, sexual or political identity. Some people still use this word as an insult – this is LGBTphobia and should be challenged.

Questioning: A person who is uncertain about and/or exploring their own sexual orientation (and/or gender identity).

There are other ways people describe their sexual orientation that are not on the list, and the language we have to describe sexuality continues to grow and evolve.

WHAT IS GENDER?

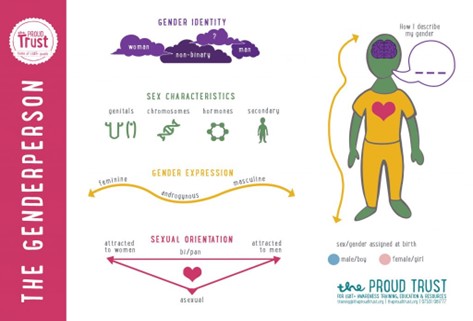

When people think of “gender”, they often think about body parts, clothes or how a person looks and acts. But we also have a gender identity. This is the gender that we identify with, the gender that we know ourselves to be and it is part of our internal sense of self.

Our gender identity can be very important to who we are as a person. Some people are men, some people are women, some people are non-binary (which means they identify as neither 100% a man nor 100% a woman). You can describe your gender however feels most comfortable to you. A trans person is someone whose gender is different to the one they were assigned at birth.

Your gender is not determined by your body parts. People come in many different shapes and sizes. Imagine you woke up one day in a different body. Would anything change on the inside? No! You would be the same person you were before, with the same sense of your own gender.

Your gender identity doesn’t mean you have to wear certain clothes or look a certain way either. Some men are very feminine. Some women are very masculine. Everyone is unique and has their own style and presentation. This is called gender expression. You don’t have to fit a stereotype of what you think a man, or a woman should look like.

You can’t tell another person’s gender just by looking at them. The only person who can really know your gender is you.

Your gender identity is about who you are, your sense of self; your sexuality/sexual orientation is about who you are attracted to. The GenderPerson is a useful tool to help you explore who you are:

From the moment we are born, most of us are treated like (and told) we are either a girl or a boy. This is called gender assignment. This can make things difficult to figure out when our gender identity doesn’t match the gender we were assigned or given.

Here are some of the words people may use to describe their gender identity. You should not feel under any pressure to assign yourself a “label”.

Bigender: A person who feels they have two gender identities – this could be at the same time or at different times.

Cis/cisgender: A person whose gender is the same or mostly the same as they were assigned at birth.

Demigender: An umbrella term for non-binary identities that have a partial connection to a certain gender. Demiboy: A gender identity that is both male and genderless. Demigirl: A gender identity that is both female and genderless.

Genderfluid: A person who feels that their gender is not static and that it changes throughout their life – this could be on a daily/weekly/monthly basis.

Gender neutral/Agender: A person who does not identify with any gender.

Non-binary: An umbrella term for gender identities which are not confined by the gender binary of “women” and “men”. Non-binary people may identify with no gender at all or with more than one gender.

Polygender: A person that has several gender identities. This can mean they have them at the same time, or that they often switch between them at different times.

For young clients and their families, having a safe space to explore their feelings about gender and sexuality is crucial, especially when society remains dominated by binary concepts and heterosexual, cisgender ‘norms’. It’s important that see young people as they see themselves.

Are we inclusive? We may think that we’re open minded and non-judgemental, but is this true of society in general, which is still heteronormative. This is a social attitude where heterosexual relationships are seen as the default or normal. We may assume people are straight, unless they tell us otherwise, or present as stereotypes of what we think LGBTQ+ people should look like, eg asking a girl if she has a boyfriend yet.

Many adults may worry that they are ‘out of touch’ and unfamiliar with some of the terms or references that young people use, or that their own experiences are different and therefore, not relevant. It can be helpful to acknowledge what and when you don’t know and looking for information or answers together can be really beneficial.

Young people are the experts of their own bodies, needs and wants, thoughts, feelings and wishes. Helping them come to an understanding of these together, rather than saying ‘it’s just a phase’, or ‘you’ll grow out of it’. Many adults are fearful of talking to teenagers about sex or sexuality, thinking this may encourage them to do it. Offering a safe place where they can explore and express their sexuality and gender identity is helpful and important, to enable them to value it in themselves.

There is not a ‘right’ age where people realise their sexuality; some people realise they are LGBTQ+ in primary school, while for others it is years into adulthood. You may also find that how you feel now changes over time – this is completely usual and does not mean you are wrong about how you are feeling now.

For example, a 14-year-old girl had begun to dress in their brother’s clothes and asked to change their name and pronouns. The child shared their anger towards parents and teachers for repeatedly using the incorrect pronouns and name. The child felt angry. Family members, friends, teachers can be confused as to the impact this can have on someone, especially where it had not mattered before to be referred to as ‘she’.

Many adults can find it difficult to understand how a person so young could make this decision and found it hard to separate biological sex from the concept of gender.

As a therapist we don’t have to try and understand or make sense of what is going on, we try to put ourselves in the shoes of our client and focus on their experiences, their thoughts and feelings in order that the client feels heard and acknowledged. This can be helpful especially if they are feeling unsupported by the adults around them as they are going through changes.

“I don’t relate to being boy or girl, and I don’t have to have my partner relate to boy or girl” Miley Cyrus

Young people growing up are inventing and embracing labels that reflect their fantasies, experiences and an internal sense of themselves, while some are rejecting all identities as inherently inadequate and restrictive and shifting to newer identities based on a more relaxed attitude to sexuality and gender.

While many of today’s young people have grown up within more accepting cultures, LGBTQ+ young people are still more likely to drop out or take time out of study, including half of all trans students. Whilst homo-, bi- and transphobic abuse and harassment remain a persistent problem for many young people. Thankfully, most LGBTQ+ young people do go on to lead satisfying, ordinary lives, yet in the therapy room we can find ourselves supporting clients acting out from a place of trauma, shame, guilt and other unprocessed, internalised beliefs connected to historic and ongoing hostility towards their gender and/or sexual identities.

It is important to recognise that, from a young age, LGBTQ+ people often have to develop sophisticated coping strategies to avoid and minimise the impact of hatred and rejection. Often subject to significant unconscious or conscious pressure from their families, friends and wider communities to be straight and stereotypically male or female, LGBTQ+ young people can repress who they are and construct what Winnicott described as a ‘false self’ to ‘protect the real self from pain’.

Adaptive strategies adopted by LGBTQ+ children can become destructive in later life, while others can actually help to build resilience in adolescence and adulthood. This can be seen in LGBTQ+ young people who are practising ‘visibility management’, where they are very careful about where, when and to whom they are out, monitoring what they say, their body language and even dating someone to ‘pass’ as straight. Such management can be particularly useful, and necessary, for many black and minority ethnic young people and those from conservative religious communities: it allows young people to be ‘out’ when they can, while keeping them safe.

“Thought to myself that all boys must like other boys and all girls must like other girls, because that is how I felt and therefore, it must be true of everyone”.

It’s important to consider how previous generations sex education at school probably didn’t include sexuality or gender.

There are gender stereotypes, boys play football and like girls; girls play netball and like boys and many young people think they should conform to this. Anything deviating from this being classed as ‘abnormal’.

Growing up in an environment that explicitly or implicitly tells you that your very core is wrong or disordered can be traumatic and overwhelming. People who are LGBTQ+ can feel shame, disillusion and disconnection, managing anxiety, depression, substance misuse, eating difficulties, self-harm and suicide, as a consequence of living in, coping with and navigating a world not designed for them.

This can impact on someone developing meaningful connections with friends, family and loved ones. Leading to an internalised sense of ‘wrongness’ because they are the odd one out and so they must change.

So, it’s important to create environments where they can be fully appreciated for who they are rather than what they are, to enable them to flourish. As it can be a big deal for a young person to feel able to safely explore their gender and sexual identity without being subject to guilt or shame.

Helpful tips

- Check out their preferred pronoun: don’t assume that ‘he’ or ‘she’ is appropriate – clients may want you to use ‘they’ or another pronoun.

- you will probably get someone’s pronoun wrong at some point or have to correct a wrong assumption about someone’s sexuality or gender. Don’t beat yourself up, because acknowledging your mistakes or ignorance can open up opportunities to find out more about what their life is like, for you to say to them, as Meg-John Barker suggests: ‘I’m not perfect, I’m really sorry I messed it up’ or just ‘I don’t know; how would you like me to refer to you?’ and thus provide what can be a meaningful, reparative experience.

All of us here at The Wellness Consultancy are here to help individuals who are struggling. Talking therapy can be a useful way to make sense of what’s going on in your life by offering a safe confidential space that can help you to develop robust coping strategies that supports a balanced mindset therefore minimise stressful situations. One to one therapy may not appeal to you and there are many other ways to access support such as in group activities, online forums, education and self help.

Helen Hyland

Child and Adolescent Counsellor

Further information:

https://thewellnessconsultancy.org

NEW Young Persons Advice Guide | Lets Talk About It

LGBT+ young people | Barnardo’s (barnardos.org.uk)

For LGBT+ Young People – The Proud Trust

Meg-John Barker – Rewriting The Rules (rewriting-the-rules.com)